by Amy L McCoy, AMP Insights LLC, and Kelly Mott Lacroix, WRRC

The dictionary definition of a tradeoff is “a balancing of factors, all of which are not attainable at the same time” and scarcity is “being deficient in quantity compared with demand”. Taken together, tradeoffs in the face of scarcity are often seen in a negative light. If there is not enough for everyone, “balance” must surely equal loss. And indeed it can. In anticipation of losses, tension and competition can become defining features in discussions of tradeoffs. The expectation of loss also fuels a greater need for clarity, certainty, and assurances that the uncertainty born from scarcity can be addressed. But what happens if instead of examining tradeoffs from the scarcity mentality, which is inherently fear-driven, we were to look at a tradeoff as an opportunity for gain in the form of a choice of water futures?

There are few places where the connection between tradeoffs and scar[ed]city in water management are more pronounced than the Western United States and the Colorado River Basin, which are under stress from drought, climate change, over-use, and over-allocation. Combined, these driving factors are leading to conditions of scarcity, where a looming Declaration of Shortage in the Lower Colorado River Basin is sparking a discussion of tradeoffs to meet a range of demands that far eclipse finite supplies.

Although P.C.D. Milly and others declared in 2008 that “stationarity”—the concept that the variability of a natural system does not change—was dead; the reality is that uncertainty has driven adaptation in water management for many decades. However, there is another side to the coin — tradeoffs offer an opportunity for self-agency and choice about how the future evolves. And importantly, if tradeoffs are viewed as an exercise of choice, they can foster agility and responsiveness as an antidote to uncertainty, as opposed to locking down on rigid rules and institutions as a response to uncertainty.

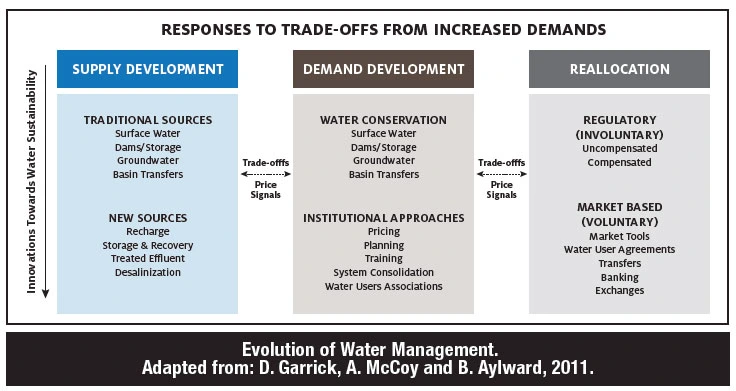

The history of water management can suggest that we have been evolving towards a place of greater choice around tradeoffs — moving from supply and demand development to the era of reallocation. Water management has evolved over time in the quest for security in the face of supply uncertainty and, in many cases, relentless growth. In thinking about water management, demand growth, and tradeoffs, we propose there are two axes and, generally speaking, three eras.

In the first of these eras demands are met using locally available supplies such as groundwater and surface water, and uncertainty in supply is managed through reservoirs or, in some cases, transfer of water between basins. More innovative approaches to supply development have included use of reclaimed water for non-potable uses, as well as recharge, storage, and recovery of imported surface water and reclaimed water. There comes a point, however, when locally available supplies are exhausted, thus initiating water management actions that include reductions in demand and/or securing new supplies. In this second era, demand management options include conservation and efficiency measures for surface and groundwater, as well as improvements in management institutions, plans, and policies to focus on reducing consumptive uses in order to extend supplies. A key tool in demand “development” is pricing water in order to reduce demand.

Eventually, however, neither supply nor demand development is sufficient to meet demands, and an era of reallocation begins. This era of reallocation can take two forms: mandatory (regulatory) or voluntary (choice-based). Under regulatory reallocation the choice of who “gets” available water supplies is made from the top down, and may not necessarily reflect a region’s values for their economy or environment. On the other hand, voluntary transactions can be seen as an exercise of choice over the course of the future. It is an act of creation to have a hand in how the future unfolds.

This is an important point for the future of the Colorado River Basin. While shortage is certainly on the horizon, it is not here yet. This means that collectively we still have an opportunity to play an active role in decisions about how the future looks and unfolds. While changes are likely to be drastic, how those changes impact us remains our choice.