The record high temperatures in June throw into sharp relief the importance of water, especially to the plants and animals that depend on flowing water for their survival. Riparian and aquatic ecosystems are among the most vulnerable systems to climate change, and as temperatures increase, so will their need for water. Yet allocation of water to ecosystems is not required under state law and, except for a few instances, is not considered alongside human uses. Considering the environment alongside human demands is only just emerging in water planning discussions.

Rivers and related shallow groundwater systems need water to survive and provide benefits to people. Ecosystem services include improving water quality, providing recreational amenities, and supporting biological diversity, among others. In addition, healthy rivers and associated ecosystems have an intrinsic value to people that may be expressed in terms of cultural significance, particularly for indigenous cultures. This intrinsic value is often overlooked as it is difficult to identify and quantify.

There are a growing number of people who recognize that water for natural areas is crucial to sustainable development and the long-term prosperity of communities. In the past decade, there has been increased interest in providing water to meet the needs of riparian and aquatic ecosystems in the Western USA. While increasingly recognized on the local level, the need to provide water for ecosystems has not been on the agenda of most politicians and policy-makers.

It can be difficult to include the needs of riparian and aquatic ecosystems in plans when other existing uses already outstrip available supplies. The water deficits that this imbalance exposes mean water managers have to be proactive in understanding both the water needs of riparian and aquatic species and community values for them if they want to maintain the rivers and shallow groundwater areas that these ecosystems depend upon. Providing decision makers the best scientific information available in a timely manner is critical.

While easy to assert, actually translating existing scientific information on environmental water needs is complex. This is in part because different species have distinct water needs and these vary depending on your location and the time of year. The water required to maintain a healthy river ecosystem is most frequently referred to as environmental flows, or more specifically, the natural flow regime. For example, to survive and reproduce, riparian trees need access to sufficient groundwater and carefully-timed flood flows for established plants and for new plant growth.

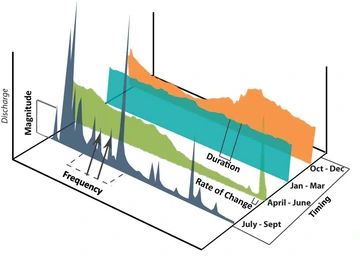

The natural flow regime consists of five elements of streamflows: magnitude (how much), timing (when), frequency (how often does a certain magnitude of flow occur), duration (how long does a type of flow occur), and rate of change (how quickly does flow go from a “peak” to a “valley”). The graphic shows what each of these elements of the natural flow regime looks like through separating an annual hydrograph of the San Pedro River into four seasons (timing) and marking similar flow patterns (frequency), where flows remain the same (duration) and a low to peak flow (rate of change). Change to any of these element of flow affects Arizona’s aquatic and riparian ecosystems if flows are altered beyond the range of tolerance of native species.

Researchers have studied the water needs of Arizona’s riparian plants, quantifying maximum depth to groundwater for survival and timing and size of flood flows for reproduction. For example, multiple studies have concluded that even mature cottonwood trees cannot survive when groundwater level declines exceed 10 feet below the surface.

Several studies demonstrate an important connection between water available to riparian vegetation and the health of insects and birds. Eighty percent of all vertebrate species in Arizona spend some portion of their life cycle in riparian areas. Others studies indicate the flow and water temperature needs of native fish. Arizona has more native freshwater species at risk of extinction than any other state. While studies of individual species are useful, lack of ecosystem level data limits the manager’s ability to ensure flows will protect the whole ecosystem.

Statewide, ecosystem-level flow requirements remain poorly understood. Most of the flowing streams in river basins across the state have not been studied. There is no simple figure that can be given for the environmental flow requirements of rivers and associated wetlands.

To date, most studies lack the quantitative data that resource managers need to understand riparian and aquatic flow needs. Only about 30 percent of streams in Arizona have quantified or described environmental flow needs. Only one river in Arizona, the Bill Williams River, has received dynamic recommendations for minimum flows for each season, ranges of flow needs, frequency, rate of change, and size of flood flows.

More studies are needed that consider the water needs of both aquatic and riparian species in tandem. Additionally, given the proven influence of groundwater on aquatic and riparian ecosystems, most river basins could benefit from additional studies of groundwater influences on ecosystem health.

Adequate science and understanding of environmental flow needs and how these systems respond to changes in streamflow and groundwater levels are essential for incorporating water for riparian and aquatic ecosystems in water management and policy. As a response to this need, to assess the state of the science on environmental flow needs in Arizona and beyond, and to create a tool for water managers, the University of Arizona Water Resources Research Center developed the Desert Flow Database. This publicly available database catalogs over 400 studies from 144 rivers across the deserts of the USA and Mexico, and is a tool for land managers, policymakers, and scientists to use when considering water for riparian and aquatic ecosystems in their management decisions or conducting their own inquiries into environmental flow needs. The database is dynamic and continues to grow as new studies are identified.

Defining the needs of riparian and aquatic species and ecosystems is the first critical step in the broader process of securing and addressing environmental flows. The ability to place the environment at the table in water management discussions, however, goes beyond the ecology and hydrology of a system. It also involves determining how much water is required to achieve a certain level of river health, a level agreed upon by the water-using community.