Water Conservation Is More Than Just Saving Water

Recently very much center stage and in the spotlight, water conservation seems to be an idea whose time has come. If, however, we define water conservation as the careful use of water to better maintain current supplies, then water conservation is not a recent development. What is relatively new is our current perception of water conservation.

Water conservation has been practiced in one form or another in what is now Arizona for a very long time, ever since the first humans arrived. Upon observing the scarcity of water in these desert lands, early inhabitants then calculated what efforts would be required to live with the available supply. They then lived their lives to fit the arid conditions of the area, taking care that the sparse water supplies were carefully and fairly used.

Now fast forward to the nineteenth and twentieth centuries: Later arrivals, now called Arizonans, also confronted desert dryness and lived accordingly, but due to their technological prowess, they soon found ways to circumvent arid conditions. In the face of water scarcity, they built concrete dams, reservoirs and canals, to capture, store and deliver water. They sought new supplies by pumping water from underground and later from distant locations.

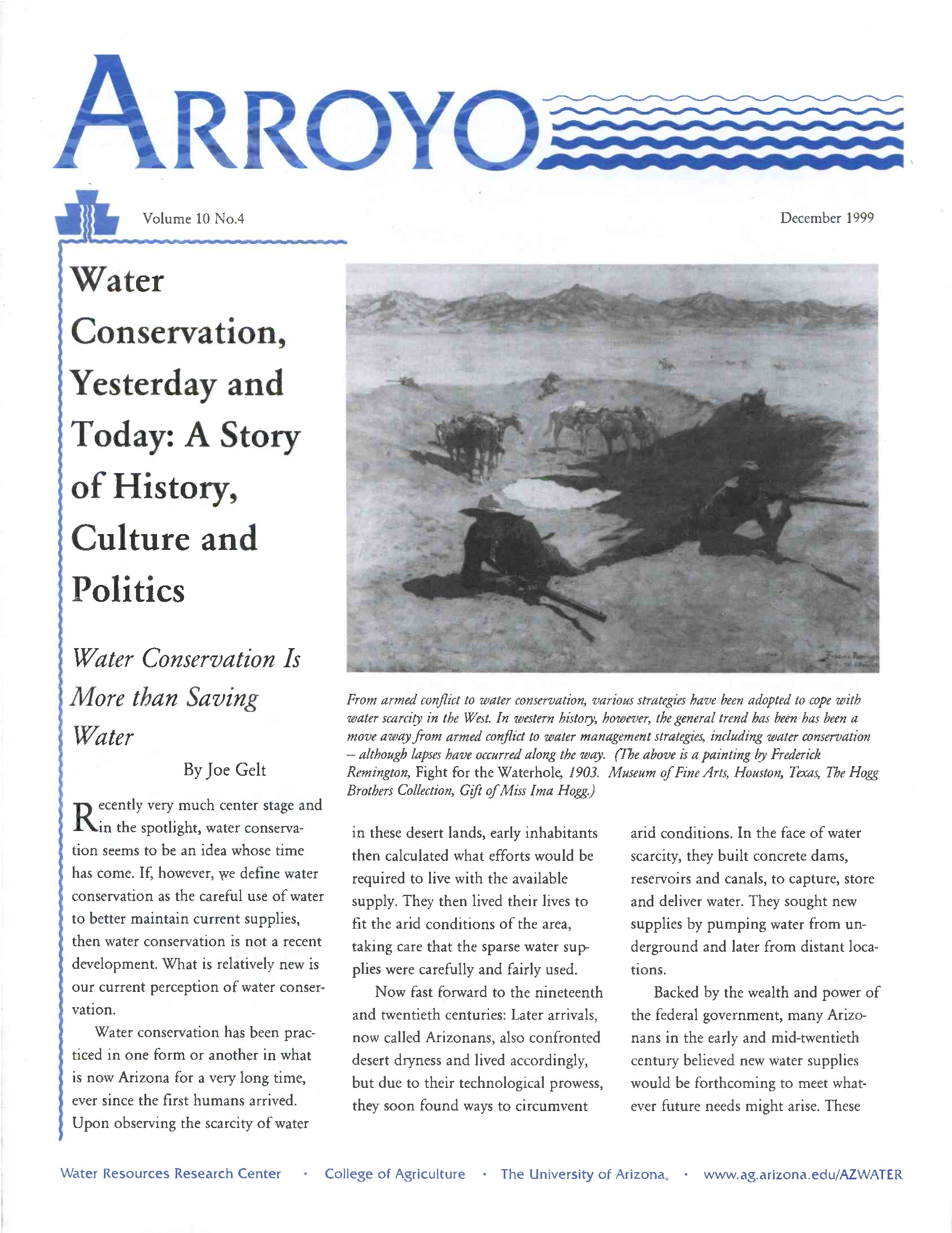

From armed conflict to water conservation, various strategies have been adopted to cope with water scarcity in the West. In western history, however, the general trend has been a move away from armed conflict to water management strategies, including water conservation - although lapses have occured along the way. (The above is a painting by Frederick Remington,Fight for the Waterhole,1903. Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Texas, The Hogg Brothers Collection, Gift of Miss Ima Hogg.)

Backed by the wealth and power of the federal government, many Arizonans in the early and mid-twentieth century believed new water supplies would be forthcoming to meet whatever future needs might arise. These were the salad days of water resources development. During these times, Arizona had as little interest in water conservation as it did in developing its own foreign policy. In fact, many Arizonans at this time likely viewed water conservation as a foreign policy.

(In truth, a utilitarian version of water conservation was being honored. Espoused by Gifford Pinchot, U.S. Forest Service head and close associate of Theodore Roosevelt, this philosophy advocated using natural resources to the best benefit of humankind, with resources developed for "the greatest good, for the greatest number, for the longest time.")

A New and Improved ArroyoThis issue of Arroyo comes with a redesigned format. Kyle Carpenter, WRRC's talented graphic artist, created what we consider to be a new and improved design. Its debut at the end of 1999 has nothing to do with the approaching millennium. It is just that after ten years of the same format a change was due. Also, with the new design, Arroyo and the Arizona Water Resource, the other |

Whatever illusions Arizonans might have had about unlimited water supplies were eventually cut short by reality. Projects to obtain additional water supplies were proving to be prohibitively costly, both economically and environmentally. Not only that, but all the available water sources had been tapped, and Arizona had run out of renewable water supplies to exploit. A federal water resource project of grandiose proportions, the Central Arizona Project stands as a monument to the Age of the Big Water Project, its last hurrah.

Water managers now increasingly turned to what economists call "demand management" or, in other words, water conservation measures. This represented a major shift in the managing of water resources. Practiced in the past to help resolve problems of water shortages, water conservation now gained official status, to be used to help resolve the dilemma of attempting to meet growing water demands with insufficient supplies. What was previously provided by new water development projects — pumps, canals, reservoirs, etc. — would henceforth be accomplished by public media messages, printed materials, education programs, rebate and retrofit device offers, landscape and plumbing ordinances and changes in water rate structures and price levels. Water conservation entered its modern phase.

|

Image

Pete the Beak Pete the Beak is the mascot in Tucson Water's Beat the Peak water conservation campaign. Pete is a very adaptable duck, taking on a new image each year. In 1987, Pete was a sax-blowing hipster, with the message that it is cool to save water. Various Pete the Beak images are found on the remainder of this website. Water Conservation as IdeaThe following brief review of the current status of water conservation in the state is to encourage a broader understanding of the concept, beyond the view that water conservation begins and ends with the do's and don't's of saving water. For example, in line with most people's understanding of water conservation, a Connecticut water utility offers a brochure titled, "Water Conservation Starts by Fixing Leaks..." As the previous discussion demonstrates, however, water conservation is more than fixing leaks, installing low-flush toilets and planting desert vegetation. Water conservation also can be viewed as an idea that has evolved over time, in response to various historical, cultural and political forces. In this light, it is not an exaggeration to consider water conservation as an exercise in democracy. Citizens are participating directly in a community cause when they practice water conservation. Unlike lawmaking, which involves citizens indirectly as they vote for candidates who then write and pass laws, water conservation involves direct citizen action. A householder either does or does not conserve water. And just as informed voters make better choices at the polls, consumers who more fully understand water conservation, its historical, political and cultural implications, are more likely to have a greater interest in saving water. Following, therefore, is a course of study of water conservation, its theory and practice, beginning with early frontier times.

|

|||

|

Arroyo is published by the Water Resources Research Center, College of Agriculture, University of Arizona, 350 N. Campbell Ave., Tucson, Arizona 85719; 520-792-9591.Each issue of Arroyo focuses on a water topic of current interest to Arizona. A list of past Arroyo topics is available upon request, and back issues can be obtained. Both list and past copies are available on the WRRC web site: (http://ag.arizona.edu/) Subscriptions are free, and multiple copies are available for educational purposes. The editor invites comments and suggestions. Water Resources Research Center |

The above families did not think of themselves as practicing water conservation. In fact, Stegner speaks of the "folklore of water" when relating his family's early water-saving experiences. Before law and public policy ruled the land, what was done to live in a land of scarce water reflected the customs, beliefs and traditions of the people settled there. Yet, at the same time, their efforts surely would meet the Environmental Protection Agency's definition of water conservation: "Water conservation consists of any beneficial reduction in water losses, waste, or use."

Such stories of life on the frontier often are told to flaunt the bravado of rugged Old West individuals, to show that they are a race apart from contemporary westerners. They may or may not have been. What the stories do clearly demonstrate, however, is that water conservation in this setting was an unavoidable task, another necessary chore to perform like planting crops and milking cows. Success at conserving water determined whether or not a family coped with frontier conditions. Further, by carefully using water, frontier folks recognized and accepted the limitations of the natural environment. The psychology of water conservation operated at a very basic level. The politics of water conservation did not yet exist.

Beat the Peak

This is Pete the Beak in 1982, with the secret words, "Beat the Peak"

Early City Dwellers Save Water

Dwellers of early urban areas — or what passed for urban areas on the frontier — faced their own challenges for getting and using water. Americans occupying the former Spanish Presidio of Tucson relied on the services of water vendors for some of their water supplies. Each morning a water vendor would drive his burros to a spring, to fill hide or canvas bags. His stock replenished, the vendor would then herd his laden burros through the dusty or muddy village streets, announcing in song that water was for sale, five cents per bucket.

Later, carts replaced burros, enabling the vendor to carry more water, thus increasing delivery capacity. More water could now be delivered more efficiently. A bucket of water sold for five cents, with payment made either at the time of delivery or weekly. Door jambs served as ledgers, with vendors recording amounts due on the strips of wood.

Early Tucsonans, however, had other sources of water when less high quality water would serve the purpose at hand. In efforts to stretch their budgets, residents reserved the pricey, five-cent water for drinking and relied on other sources of water for various household uses. For example, wastewater irrigated trees and gardens, and Santa Cruz River water would be fetched for bathing and laundry.

Viewed in a modern context, the water vendor might be considered the precursor of a water utility. Early residents of the Old Pueblo now become water consumers. This is a significant moment in the history of water conservation in the state, with both water provider and water consumer sharing an interest in the economics of water. The water vendor or provider seeks profits, and residents want the most goods or services from their expenditures. Water conservation becomes an economic strategy to help balance the household budget. In this context, water becomes mainly a commodity. The folklore of water is replaced by the economy of water. Early Tucson residents appear to be practicing water conservation partly as we understand the concept.

(Perhaps two stories of Saturday night baths might dramatize this difference in attitudes about water, between water as a respected and valued resource and water as a commodity. Previously, Juanita Brooks was quoted describing how Saturday bath water would serve several needy bathers before being used for laundry and cleaning, then to water plants. In Flagstaff, another kind of bath-time ethic arose. Local legend tells of the custom of checking downtown saloons on bath night for neighbors with piles of chips before them. Such individuals were likely to be long occupied in playing poker. Their unguarded water barrels were soon emptied to provide an ample and luxurious bath to an unscrupulous opportunist. Both of these accounts are of people taking best advantage of available water resources, but with a striking difference.)

|

U.S. Population Up, But Water Use Down Individual water users who wonder whether their conservation efforts really add up to much should take heart. Recent statistics show that despite a steadily increasing U.S. population, the nation is using noticeably less water. Compared to the record high consumption of almost 20 years ago, the United States is now saving 38 billion gallons of water per day. This is enough to fill Lake Erie in a decade. According to U.S. Geological Survey statistics the nation is consuming 402 billion gallons per day for all uses. This is 2 percent less than in 1990 and nearly 10 percent less than in 1980. The USGS has a compiled and reported national water-use statistics once every five years since 1950, using millions of figures supplied by state agencies. The above figures represent the period from 1990-95 and were released late last year. The USGS figures show that from 1950 to 1980 water use continually increased, and since the mid-1980s water use declined. "The nation is clearly using surface and groundwater resources more efficiently," says Robert Hirsch USGS chief hydrologist. "Enhanced citizen awareness of the value of water and conservation programs in many communities across the country have helped cut water use in spite of continued population growth." Although individual householders have indeed done their part to conserve water, agriculture and power generation have the biggest effect on total water. |

Individuals engaged in conserving water to maintain life on the frontier might represent a personal commitment to careful water use. With increased settlement and with more people competing for limited water resources, water use became a community concern and cooperation a necessity, for one and all to survive. When agreements or laws were worked out to determine water use, community attitudes and values played an important role. Since water conservation is the flip side of water use, examining these attitudes and values will provide some clues to understanding certain public responses to water saving strategies in this region.

Water and Culture

Depending upon the perspective, water can take on many meanings, whether interpreted by a hydrologist, a lawyer or a farmer, to name just three interests. Not often thought of as a commentator on water, an anthropologist also might have something to say on the subject. This is because water can be thought of as cultural artifact, with various cultures and societies interpreting its significance differently. For example, three early cultures to have inhabited Arizona and the Southwest — Indian, Spaniard and American — valued water in different ways. A brief discussion of how each of these cultures valued water will show some compatibility and incompatibility with modern water conservation sensibilities.

Indian In many traditional Indian societies water had a spiritual significance and was prominent in myth and ritual. Rain might be considered a blessing and drought a punishment, with humans benefitting or suffering depending upon what they did or failed to do. For example, the Tohono O'odham perform a saguaro ceremony to bring rain.

For some tribes, nature had an intrinsic value unto itself, beyond whatever physical benefits it provided humans. Some tribes even attributed thoughts and feelings to animals, plants, stones and springs. More than a physical reality of various categories

— water, minerals, plants, and animals

— nature formed an interconnecting web,

with the boundary between the human and nonhuman not always clearly drawn. Some tribes even believed that humans, through their own efforts or the machinations of others, can take on the form of rocks or become trees, coyotes, fish, ducks or other creatures.

The idea that water can be owned, to be bartered or sold, was foreign to many Indians. Water like land transcended the needs or desires of any individual, or even group of individuals; instead water was an essential element of nature to be shared by humans, animals and plants.

Spanish To the Spanish, nature was not sacrosanct. What it bestowed — rivers and streams, woodlands, minerals, soils and animal and plant life — might be considered a divine gift, but one to be subdued and exploited for the glory of God and civilization. Las Siete Partidas, a 1265 codification of Spanish law used as the basis for the legal system in the New World, stated, "Man has the power to do as he sees fit with those things that belong to him according to the laws of God and man." Above all else, however, water was to be used to ensure survival of families and local communities.

To the Spanish, ownership of water was not a troubling issue. Spanish law clearly determined the crown to be the preeminent owner of lands and waters in the New World. The crown, or more likely its designees, could either grant ownership or merely temporary use. Until such allocations were made, New World settlers shared the royal patrimony.

Adopted about 1783, the Plan of Pitic defined community water rights along what is now northern Mexico and the U.S. Southwest. Basic to the plan was the right of all citizens to share the town's water, along with other natural resources. Since water was for the benefit of all, no one possessed a superior right, to be applied to the disadvantage of fellow residents. Neither a person nor a family could claim rights to specific volumes of water. The quantity varied according to individual and community needs and the available supply.

Americans With the Americans came another understanding of water, one more suitable for a nation of individuals, with each citizen believing in a right to pursue a personal destiny, even if the quest is not in the best community interest.

To the Americans the western lands were a treasure trove, their gifts for the taking. Like the Spanish, the Americans valued the environment, not because of any intrinsic values of its own, but as a means of political, social and economic gain. An essential difference between the two cultures, however, must not be overlooked. Hispanic culture was more communal, with a greater reliance on authority, both God and king..This view contrasted sharply with the American tradition that believed in individual rights and minimal governmental interference.

Conditions in California seemed to favor this latter approach. Government institutions and authority were remote, and miners confronted immediate problems. For example, miners needed water for various mining operations. The land might be blessed with minerals, gold being the most desirable, but water was needed to extract the precious metal. Water supplies, however, were limited, with relatively few rivers, and precipitation was infrequent. Further complicating the problem, the ore-bearing soil often was located at a distance from a stream or river, frequently many miles. The obvious solution was to divert water from its source, and miners, ever hopeful of striking it rich, did divert. They expended great labor to build "wooden sluices, iron pipes, ditches, and whatever else that worked."

What became obvious to all, even to the most hell-bent, self-serving prospector, was that uncontrolled or unregulated diversions meant ruin. With no advice forthcoming from government — nor, of course, was any desired — miners set out on their own to allocate water. According to frontier tradition, an authority miners respected, those who arrived first possessed superior rights. First applied to land and mineral claims, this principle also served for water and became the foundation of the prior appropriation doctrine.

Usually summarized by the aphorism, "First in time, first in right," the prior appropriation doctrine ensured that those who first used water could not be deprived of their rights by latecomers. Maintaining this privileged water right involved certain minimal requirements; i.e., a water user must continually use the water for a beneficial use. Beneficial use at first meant mining, but was later applied to agriculture, manufacturing and other purposes deemed to be beneficial. Arizona surface water law is based on prior appropriations.

The prior appropriations doctrine represents one of the earliest official strategies of allocating scarce water resources among competing water users in the American West. The doctrine is based on an assumption that remains active today: i.e., water is a commodity to be used, its value determined by whatever material benefits are gained through its use, whether corporate profits or a residential swimming pool. This assumption is a thread that runs through much of western U.S. history and is a challenge to water conservation efforts today.

Tapping the Hidden Waters

Water conservation is linked to water use. Water being a finite resource its excess use and the resulting shortage often prompts efforts to conserve it. More than surface water, which is regulated by the prior appropriations doctrine and its water-consuming rationale, groundwater, its development and exploitation, provides a study of an awakening awareness of the value of water conservation.

In early Arizona history, reliance on surface water sources limited human ambitions, especially of those settlers anxious to take up ways of life that flourished in other parts of the country. Surface water sources available from the few Arizona rivers and streams would not be sufficient to enable urban areas to grow and flourish and agricultural operations to expand. What was needed was another source of water to enable settlers to develop what they believed to be the full potential of the region. Groundwater was this other source of water.

Groundwater use would eventually raise serious concerns about depletion and the need to conserve water. Preserving groundwater resources would be the cause to involve state government in water conservation, with laws passed at various times in efforts to regulate groundwater withdrawal. Also of significance, pumping groundwater required major technological innovations, thus raising an important issue — the use of technology in developing water resources. All this would come later; at first, however, groundwater was a limited and a generally inaccessible resource.

Early settlers in the area were aware of the existence of groundwater. Spaniards had dug wells in areas with a high water table. In fact, water tables were sufficiently high in early Tucson history that wells were fairly common.

Around 1870, windmills began to be used, tall, gangling structures with rotating blades to bring groundwater to the surface. An early account of Tucson at this time describes most homes and business as having windmills to provide individual sources of water. Historian Walter Prescott Webb wrote, "The windmill was like a flag marking the spot where a small victory had been won in the fight for water in an arid land." It would seem that Tucson was celebrating a string of victories within its desert setting.

Hand-dug wells and windmills provided settlers with rather limited groundwater supplies since their subterranean range was rather shallow. Steam powered pumps, in use by the end of the nineteenth century, allowed greater access to groundwater. In 1899, the Tucson Water Company's first steam-driven pumping plant could pump 1,250 gallons per minute from a 40-foot well. Pumping technology continued to improve, and in 1914, new and improved pumps were installed for use in six wells, each capable of pumping one million gallons of water per day from greater depths than were previously tapped.

Previously mostly out of reach, groundwater, seemingly a buried treasure, now appeared to be a plentiful resource, at first benefitting mainly Arizona agriculture, but with urban areas soon getting their generous share too.

The 1920s were boom times for Arizona farmers. Not only were pumps becoming more efficient, but the power to work them was inexpensive. Meanwhile cotton prices increased. Good judges of the prevailing weather, economic as well as climatological, farmers took advantage of these favorable conditions to plant more and, as a result, to pump more. Then a drought in the 1930s raised water consciousness in the state. Concerns about excessive groundwater use were raised, and efforts to control pumping began to be taken seriously. Water conservation emerged as an issue.

|

Image

In 1993, Pete the Beak was a rock n' roll Elvis impersonator. Regulating the Use of GroundwaterWith a number of farmers drawing great quantities of water from a common source, a different strategy was needed than what prevailed during frontier days when settlers regulated and managed their own water supplies. A successful conservation program at this larger scale called for an enlarged regulatory and water management role. Government took up the challenge and intervened, and the politics of water conservation emerged. Government regulation can be tricky business in Arizona. It is often viewed as intrusive and against the pioneering grain of the independent and self-sufficient settler, at least as this figure is understood in popular culture. For example, legislative hearings of 1947 regarding proposed groundwater legislation elicited the following remark from a farmer: "Who is going to tell me what to do and how to do it? If my land is destroyed through lack of water I want to destroy it myself; I don't want you to do it." This defiant statement expresses an attitude to contend with back then and to be considered even now, especially when regulation of natural resources is at issue. By the early 1940s, various proposals were made in the Arizona Legislature, for studying, writing and passing a groundwater code. Realizing it was to its benefit, the agricultural sector took a special interest in the passage of a groundwater code, with the Arizona Farm Bureau Federation calling for a code as early as 1942. A U.S. Geological Survey study of major groundwater basins at this time provided further evidence of the need for legislative action. The agency found in one especially heavily developed area of the state the annual safe-yield was being exceeded by 18 times. Safe yield means a long-term balance between the amount of groundwater pumped each year and the natural and artificial recharge occurring annually.

Meanwhile groundwater pumping continued apace. Pumping technology advanced after World War II, making it economically feasible to pump water from depths of as much as 500 feet to be used for growing cotton, vegetables and citrus. The result was an increase in irrigated acreage, from 768,000 acres in 1945 to 1,279,000 acres in 1953, occurring mostly in areas of the state dependent on groundwater. Growing concern prompted the Legislature to enact the Arizona Critical Groundwater Code in 1948. The 1948 law, however, was deemed deficient by all concerned, its recognized purpose to slow down the rapid depletion of groundwater, not to solve any long-range safe-yield problems. The new law sufficiently rankled Representative Murphy of Maricopa County that he mixed his metaphors in his displeasure. He said the code was "as weak as restaurant soup and should have been sent from the Senate with crutches." As expected, the 1948 Code proved ineffective. Enforcement was lax due to budgeting problems, and various legal skirmishes ensued. And, most troublesome of all, the rate of groundwater withdrawal increased. Studies and recommendations followed, all to no effect. One more effort to pass an effective groundwater code came to naught in 1954 when the Legislature failed to act. For all practical purposes no effective regulation of groundwater pumping was in place until the passage of the Groundwater Management Act in 1980. In the meantime, instead of government regulations, short-term economic considerations ruled; i.e., pumping costs, not conservation, determined groundwater exploitation. 1980 Groundwater Management ActConcern about groundwater overuse again made the legislative agenda when the Groundwater Management Act was passed in 1980. The Arizona Legislature passed the law at the urging — some claim it was in response to a threat — of the federal government. Whatever might have transpired between the two parties, a bargain was in fact struck: the state would take measures to control groundwater use and the federal government would complete the Central Arizona Project. The GMA was the result of political maneuvering, and water conservation became the law of the land. The GMA stands as the cornerstone of the state's water conservation efforts. With the GMA, serious efforts to conserve groundwater were now to be undertaken, backed by the power of the state. The Arizona Department of Water Resources was established; its responsibilities included devising and administering mandatory conservation measures in various areas of the state. Groundwater use in designated areas now would be carefully regulated, with management plans outlining specific conservation goals for various classifications of water users — agricultural, municipal and industrial. That the state became a major player in determining water use in declining groundwater areas represented a major departure from previous conservation strategies. The GMA established four Active Management Areas. AMAs are areas with severe overdraft problems, and the original AMAs are Phoenix, Tucson, Prescott and Pinal County. Later in 1994, the Tucson AMA was divided to form a Santa Cruz AMA. AMAs contain about 80 percent of the state's population, with 70 percent of the overdraft occurring in these areas. The primary management goal of the Phoenix, Tucson and Prescott AMAs, the most populated areas of the state, is to achieve safe-yield by the year 2025. The AMAs are to accomplish their safe yield goal by developing and implementing a series of five management plans over time, with the first occurring 1980-1990; second 1990-2000; third 2000- 2010; fourth 2010-2020; and fifth 2020-2025. Each management plan is to establish water conservation requirements for the different categories of water users. In general, the requirements become progressively more stringent with successive plans as the AMAs progress toward the safe yield goal. If all goes according to plan, each successive management effort will represent a greater measure of groundwater saved. Along with putting various types of water users on notice that they are obligated to conserve groundwater, the GMA granted generous regulatory powers to the AMAs to ensure that water users adhere to water saving management plans. For example, an AMA can set irrigation efficiencies for each farm unit within its jurisdiction.Residential water use is classified as a municipal water use and represents a significant amount of water. For exam-ple, municipal water use in both the Tucson and Phoenix AMAs is approximately 40 percent of total water used within each AMA. Of that percentage, residential water use makes up about 60 to 64 percent. Although the GMA may not be a household term, the effects of the act are felt by domestic or residential water users. The act sets conservation requirements that must be met by municipal water providers or water utilities, with individual targets set for each municipal provider based on water use patterns within its service area. Municipal water conservation goals are measured as gallons per capita per day (gpcd). To help meet gpcd goals, water providers encourage their customers to practice water conservation. Utilities accomplish this task through various outreach efforts, including public media messages, a plethora of printed materials, education programs, and rebate and retrofit device offers. Water rate structures and price levels also might be altered to increase the economic incentive for householders to save water. Unlike income tax laws, for example, the GMA does not impose a legal obligation directly on individual water users or citizens. Instead, conservation goals are set for water providers, who, in turn, encourage consumers within their service area to use water wisely. Unlike the 1948 groundwater code, the GMA is believed to be more hearty than restaurant soup and able to stand on its own in many respects. Yet questions have arisen about the GMA's effectiveness at promoting water conservation, both in the long view of achieving safe yield and in the more immediate task of enforcing water savings among the state's water consumers. Various loopholes in the law and Arizona's rapidly growing population may mean trouble ahead, with greater and more frequent water shortages. A recent state auditor general's report cast doubt on the state's ability to achieve safe yield in Phoenix, Tucson and Prescott AMAs by 2025 as planned. One of the criticisms of the GMA is that it measures water savings by gpcd. In effect, this means the law seeks to decrease the amount of water each person uses, without taking into consideration increases in population. If water consumers each use less water while at the same time total population expands, a net increase in water use could result. At one level water conservation goals might in fact be met, but in the broader view a larger population means more water will ultimately be consumed. Critics ask, "Where then is the water savings?" Critics also question the effectiveness of the GMA regulating utilities or water providers as the means of promoting water conservation among water consumers or "end users." Utilities are basically in the business of providing safe, affordable water and lack the authority to pressure customers to save water. Some critics say regulatory efforts might prove more effective if targeted directly at the end users, resulting in greater water savings. The GMA directly regulates water users in the agricultural and industrial sectors, and a similar approach could be applied to the municipal sector. Water Conservation for What? Questioning the purpose of water conservation might seem to belabor the obvious. This is because water conservation often is perceived as an unqualified good, its cause just, its methods fair and its motives pure. (A Southern Arizona Water Resources Association newsletter stated: "Water conservation is like motherhood and apple pie ... something we know is innately good, especially when we live in a desert.") Yet, differences of opinion exist about the rationale behind water conservation programs and even whether such efforts are, in fact, needed. To some people water conservation is a solution to a problem that does not exist. If they live in Tucson, they may observe that life goes on in the city, seemingly not inconvenienced by a lack of water. Not only are present residents well supplied and well watered, but evidently there is enough water to spare for ongoing growth in the area. People living in the Phoenix area may feel comforted by the series of reservoirs storing water above the city, to be released upon demand to head off any threats of shortages. Why take on the burden of conservation when water seems not to be a problem? Others consider water just another commodity, its consumption determined by perceived need and the ability to pay. According to this scenario, people need not be frugal with water if their preference is for lush landscaping, backyard swimming pools or full-flowing toilets and faucets. Why should such people suffer the inconveniences and discomforts of water conservation if the way they choose to live requires heavy water use? Who is to say that native vegetation is preferable to turf? Such people believe that their willingness to pay for excess amounts of water entitles them to whatever quantities they desire. Still others are guided by what they perceive to be a higher set of principles that values water beyond supply and demand and its direct use. That water is a scarce resource in a desert environment means water is to be used carefully in such areas. Even where relatively plentiful, water is still valued as a natural resource, to be respected and used wisely. As Helen Ingram wrote in her book, Water and Poverty in the Southwest, "This is not a rational choice to plug leaks and fix leaky faucets, but rather a deep feeling that waste or excess is incompatible with and even irreverent toward such a valuable and fundamental part of the environment." To such people water conservation is not a strategy, but an ethic, best understood as conforming to a system of moral principles or values. Others argue they would gladly conserve water except they are wary that their efforts might not be put to good purpose. They believe water conservation is a good cause made at times to serve questionable ends, even used to accommodate additional growth and development. They fear that water savings resulting from residents getting by on less water might mean more people moving into the area, to share supplies freed up by the conservation efforts of others. Suspecting a hidden — or not so hidden — agenda favoring growth and development in a water conservation program is justified, both from an historical and also more contemporary perspective. The presence of such an agenda rankles those whose commitment to water conservation follows much different lines. For example, if you believe that saving water is an inherent good in itself, you may resent water conservation used as a strategy to favor growth and development. This, however, might be a reflection of modern sensibilities. Other views prevailed in the past. In 1989, Sherriff Pete the Beak was on the lookout for water wasters. Don't let him catch you watering about sundown Water Conservation Serving GrowthImage

In 1989, Sherriff Pete the Beak was on the lookout for water wasters. Don't let him catch you watering about sundown As early as 1892, the Tucson City Council was discussing what could be considered water conservation measures. At that time, the council debated limiting irrigation to nighttime hours due to water shortages. The ordinance did not pass, but the mayor did order the water supply to city parks shut off. A decade was to go by before the Council passed in 1903 an ordinance limiting irrigation to between 5 a.m. and 8 a.m. and between 5 p.m. and 8 p.m. Violators could be fined a maximum of $50, a significant sum at that time. In 1920, again confronting water shortages, the Council voted to limit watering to certain hours. It was at this time the Council hired a staff person to provide water conservation information to the public. What prompted the Council to take action was a growth issue, at least as understood in those frontier days. In that now-seemingly innocent time, growth was not considered a threat to water supplies — i.e, aquifers or streams. Instead, the problem was increased population outgrowing the ability of the utility to deliver needed water resources. As a result, water conservation was stressed not to preserve supplies, but as an interim measure while the utility expanded the water delivery system. A notice in a Tucson paper makes this point clear. Dated June 6, 1903, a "Notice to Water Consumers" states, "Owing to the increased consumption of water so far in excess of the present means of supply, and the decrease in the underground flow to the now existing wells, it becomes necessary to curb the sprinkling and irrigation of lawns and trees, until the installation of the new pump ordered by the city." The notice included names of members of the Water Committee and graciously concluded by "...trusting that the fair-minded citizens of Tucson will bear with us in this proposition." ConclusionA variation of the above theme is to promote water conservation to avoid the financial burden of expanding present facilities, at least for the time being. In this situation, the need to expand the water delivery system to meet the demands of growth is put off by encouraging conservation. In other words, water conservation is a stopgap measure, to allow business as usual, without the utility expending great sums of money on capital expenditures. Some critics claim this was the rationale behind Tucson establishing in 1977 its Beat the Peak water conservation program. At the time it was considered an innovative program to control water use, and it attracted national attention. The Beat the Peak program resulted from a political debacle, with a party in power deposed over a water rate increase that was intended, among other things, to control growth. Although pledged to roll back water rates, the political victors subsequently retained the increase. Once in power, they discovered that not only was the increase justified but, contrary to the original intent, the higher rates would provide funds to increase water supplies and expand the distribution system. This would benefit future population growth. The Council, therefore, further raised the rates and for good measure initiated a water conservation program. The Beat the Peak program thus was launched, to help manage peak load by urging citizens not to water between 4 p.m. and 8 p.m. This was to save Tucson Water, the city water utility, from having to make large capital expenditures, to the advantage of the city's bonding capacity and its potential for future growth and development. An argument to secure Beat the Peak funding stated for every dollar spent on its media message $1, 000 would be saved on further capital expenditures. The Beat the Peak program has changed with the times. Still in operation, the program urges other reasons for saving water than to delay the need to construct new reservoirs. The program has adopted law-abiding sensibilities, urging water conservation to meet the legal mandates of the GMA. Water savings also are urged by appeals to a desert environmental ethic. Conclusion Discriminating practitioners of water conservation know there is more to water conservation than saving water. Saving water is the end result, the final product of the workings of various historical, cultural and political influences. These determine our perceptions of water, water use and therefore our commitment to water conservation. For example, water conservation can be folklore, a strategy to support growth and development, a method for providing water for "the greatest good, for the greatest number, for the longest time" or an action mandated by law, among other things.

How is the current age to be defined? One development to set it apart is that water conservation seems to have come of age. It is a serious water policy issue to consider, at the national and even international level. At the same time, water conservation has gained popular recognition as a cause deserving of consideration and commitment. That water conservation can play an important role in managing our water resources is now readily acknowledged. What is meant by water conservation has changed over time, its meaning having evolved in response to varied circumstances and needs. To characterize water conservation today, however, aside from pointing out its greater popularity, is difficult. This is because ours is an eclectic age, more so than other periods of the past. Water conservation is supported and practiced today for varied reasons. Yet, if we were to identify one strand that stands out today, a belief that might characterize water conservation in our time, it would be an acceptance of a water conservation ethic. More people are now aware of the environmental costs of securing increasingly more water resources. Desert dwellers are especially sensitive to the ecological incongruity of exploiting water resources in an arid environment. Meanwhile a global water shortage looms, threatening the health and well-being of a vast number of people and the economic security of nations. An awareness of these circumstance serves to raise people's consciousness about water and its use. Along with whatever economic or psychological satisfactions people derive from fixing a leaking faucet comes the glow of knowing that they did the right thing. |

|||