I have lived in Arizona for close to 42 years. When I moved to Arizona from New Jersey, where I grew up and was educated, I had no idea I would become a water professional. I studied economics as an undergraduate at Rutgers University and as a graduate student at Princeton University. My fields of specialization were Public Sector Economics (the economics of government tax and expenditure policy), Econometrics (using statistical methods and models to characterize economic behavior), and International Economics. Note the absence of anything sounding like water, agricultural, or environmental economics.

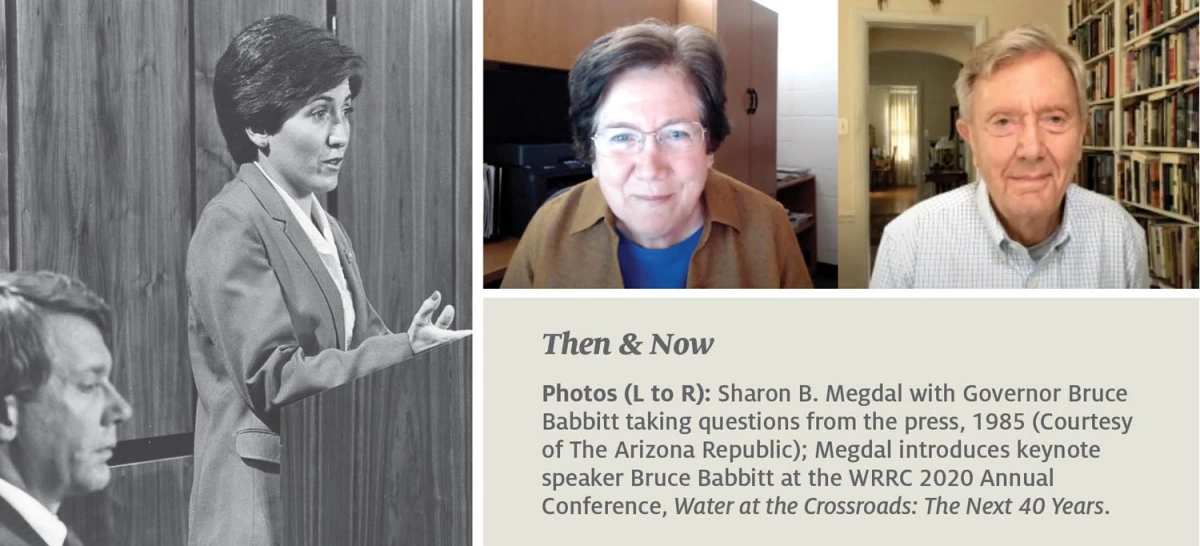

Some interesting twists and turns in my professional career led me, since the early 1990s, to focus almost exclusively on water. The most pivotal event occurred in September 1985, when Governor Bruce Babbitt appointed me to fill a vacancy on the Arizona Corporation Commission (ACC), the body responsible for regulating privately owned utilities. I was therefore especially pleased to publicly thank Mr. Babbitt at the WRRC’s June 2020 annual conference for profoundly influencing my career.

Recently, when scanning some publications from the 1980s, I came across a document I had totally forgotten: the proceedings of the October 27-28, 1987 Arizona Futures Symposium. My speaking assignment at the symposium was to react to Robert Theobald’s comments, entitled “A Framework for Thinking About Transportation Issues.” I was asked to focus on economic issues and Arizona’s future carrying capacity. Robert Theobald (June 11, 1929 – November 27, 1999) was a distinguished consulting economist and futurist author. In October 1987, I had the experience of ACC service and my economics training to draw upon. I was a self-employed consultant and part-time Visiting Associate Professor at Northern Arizona University, teaching economics for NAU’s MBA program.

As I reviewed the transcript of my commentary, I found portions pertinent to our situation today and our quest to address wicked water problems. To acknowledge the 35th anniversary of my appointment to the ACC, I would like to reflect upon observations from that time, specifically my 1987 symposium commentary. Perhaps you will find my comments relevant to some of our current-day water policy challenges and efforts to identify pathways to solutions and conclude, as I did, that “the more things change, the more they stay the same.”

In late 1987, we were in the transition from the industrial era to the communications era, just a few years after the break-up of AT&T, the monopoly that provided most of the country with telephone service. These were uncertain times for the telecommunications industry. Judge Harold Greene, who presided over the breakup, wielded a lot of power. I asked the question: “Can we rely on the Judge, the state and federal regulatory bodies, the companies involved, and the market to coordinate so that the communications network develops in an appropriate fashion? There are some who are quite pessimistic about the answer to this question. The infrastructure we will have in place to handle our transportation and communications needs will depend on many parties and many actions, and is not likely to be ‘optimal’.”

I pointed out that communications and transportation systems can be substitutes, something we are so keenly aware of now that COVID-19 has upended our work, educational, and personal lives. Then, teleconferencing and facsimile transmission were two examples of how the communications network could be used instead of the transportation network. Who would have imagined that we’d have the virtual meeting platforms we now have?!

When looking toward the future, I asked: “What will make things change so that a farsighted public policy replaces the crisis management spirit that pervades so much of government’s – and the private sector’s – operations? We are talking about things that require a long lead time. Shorter run problems require more immediate attention and resources. How can a community that cannot determine its carrying capacity in the short run (or does so only by default) ever find the resources to devote to longer term problem solving?” I noted the need to “formulate the questions now and educate the public – including decision makers – on the questions and also on the future implications of current decisions. Too often we search for answers when the questions have not even been properly articulated.”

Drawing upon the fiscal federalism framework that has shaped my thinking about a multitude of public policy matters, I spoke about jurisdictional responsibility. “What level of government should have the responsibility of dealing with these issues? We live in a federal system of states, counties, cities, school districts, improvement districts, etc. Arizona is made up of many different regions, each with its own character and problems and, therefore, solutions. Most observers of demographic and economic trends point to the disappearance of the bell-shaped income distribution. Instead we see a bimodal distribution – lots of poor and lots of well-to-do, with little in between…How will such an income distribution affect social and physical infrastructure requirements?”

Whether transportation, water, or other governmental responsibilities, I have long been interested in the diversity of situations. I suggest to you that these 1987 observations could be made today and in the context of water: “Economic conditions vary not only within counties, but also between counties. There is already a feeling within the state of the ‘haves’ and the ‘have nots’. Fiscal constraints are going to be no less important [in the future] than they are today. In fact, they may become more severe.” I further observed that “the challenges of developing appropriate policy for the future will necessitate cooperation among many levels of government and between the private and public sectors. I think this is a reality that must be recognized.”

I ended my remarks with some statements that I again suggest have relevance to today’s water policy dialogues. “What can be done so that we have a chance of choosing a policy vector that leads us to a desirable future? We must recognize that we are borrowing from future generations so that we may have today. We are borrowing for things we should not be [borrowing for] and not borrowing for things (such as building of infrastructure) that we should be. There are no easy solutions. We have difficulty solving today’s problems. Management is rewarded on quarterly profits. Elected public officials are judged on what they did while in office, not on the basis of what they might have done for the very long run.”

I am going to end this essay as I ended my commentary. I have been consistent in my call for education at all levels and in acknowledging that both the private and public sectors have important roles to play in resolving our thorny public policy challenges. “I am convinced that more resources have to go into public education on issues related to our future. There needs to be a continual effort to formulate questions and discuss issues and potential solutions…The commitment of resources will have to come from the government and the private sector, as both have a stake in our future.”