by Joe Gelt, Former Arizona Water Resource Editor

Ancient wisdom being ancient wisdom might not offer solutions to contemporary problems. But then again one should not underestimate the power of ancient wisdom to give moderns something to think about. We need all the help we can get.

With that in mind consider the words of Lucius Annaeus Seneca (4 B.C.E. – 65 B.C.E.): “Where a spring rises or a water flows, there ought we to build altars and offer sacrifices.”

Among the many and varied water resource tasks keeping hydrologists, engineers, lawmakers, lawyers, economists, et al. busy, the building of altars and the offering of sacrifices are not likely high on their things-to-do list.

(I personally believe sacrifices at altars might be worth a try, realizing at the same time this is not a strategy likely to gain public favor. [I’m aware, however, it is risky business to presume to know what might win public favor.] An altar set up on the commons, an appropriate sacrifice offered for the public good. Where’s the harm? It might bring rain.)

Perhaps Seneca’s words, however, should not be taken quite so literally. What the Stoic philosopher was getting at with his talk of altars and sacrifices is that water is a holy and essential substance and is deserving of reverence, its occurrence a cause for celebration and devotion.

To talk today of water’s spiritual and aesthetic qualities may sound hollow to our tin ears attuned to a materialistic view of world. Such highfalutin thoughts may be viewed as philosophical and aesthetic meanderings, at odds with the utilitarian ethic of water prevailing nowadays.

What I think is called for is a new understanding of water, a new sensitivity about its meaning and power, an increased appreciation of its joys and pleasures.

To some extent people are already aware of water’s universal appeal. Dull and doltish are those who have not experienced awe when viewing the ocean, who have not admired the natural beauty of a stream or lake, who have not felt a rush of excitement at a powerful waterfall.

Water is all this and more, the more involving what might seem to be pretty prosaic stuff. Water flows from our faucets in our homes. Can some of the magic and mystery of water carry over into our daily use of the substance? Water unbound and bound—but water nonetheless.

I’ve attended my share of water conferences, read a lot of water literature and have encountered an oft mentioned complaint. I call it the “Water Pro’s Lament.” It will be said, not without some justification, that as long as folks can turn a valve and water flows from the faucet they are satisfied.

In other words, their water expectations and curiosity begin and end at the faucet. All the labors that transported water to the faucet, the engineering and administrative complexities and chores, are little regarded, if at all. Understandably this causes hurt feelings.

I feel the water pro’s pain, but by temperament and interest I am moved more by what I call the Poet’s Lament: that water users use water without awareness and appreciation of the folklore of water, not fully aware that water is the sap and juice of the earth, its wash, ebb and flow the source of life, a substance of beauty, joyfulness and spiritual solace.

Is it too much to ask that water users develop water mindfulness? Is it that they already have too much on their minds? And what will be gained if they do become more water enlightened?

For one, water conservation might be practiced with a deeper understanding and involvement. Water officials bemoan citizens’ limited interest in water resource management, but one aspect of water policy that requires the direct participation of water users is water conservation. To save water or not to save water—and how and to what extent—those are the questions confronting all water users.

Those who respect and cherish water, who acknowledge its power and influence in their lives, are more likely to be committed to conserving water. I think this is true of preserving any natural resource: it begins with love and respect. The thrill of water rushing in a stream or arroyo, the smell of rain in the desert, such occurrences should be the inspiration behind any desert water conservation program.

What is needed to raise water consciousness? What will create new currents of water thinking? It will be no single item from the grab bag of possibilities, but a number of things. The intent of whatever is done, however, would be to celebrate water in a richer and more diverse fashion, beyond the eternal cycle of use and reuse, beyond the strictly utilitarian. Creativity is called for.

An event along this line was an evening of water music and narrative conducted by Water Resources Research Center’s Associate Director Claire Zucker. Zucker, a watershed planner and musician, and her bandmate Dave Firestine wove together a variety of historical and current water topics with songs and traditional tunes.

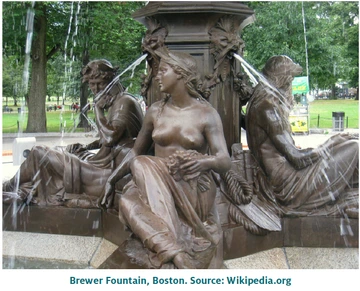

Consider also water fountains. Water fountains can also contribute to the cause of celebrating a higher appreciation of water. In fact, I don’t think it is farfetched to consider fountains water altars. Seneca would likely agree.

Fountains can be designed to display water in a way that expresses or interprets the physical and aesthetic reality of a locale or region. Consider Portland’s Ira Keller Fountain. It holds 75,000 gallons of water with 13,000 gallons cascading through it per minute. It was designed to suggest the abundant waterfalls in the Northwest.

In contrast, in very great contrast, a fountain expressing a desert water aesthetic was in Paolo Soleri’s Scottsdale studio. It consisted of a pipe slowly dripping water into a stone basin. The drip never fills the basin, which does not have a drain, because the rate of evaporation matches the slow regular dripping of the water.

This slow and restrained water display demonstrates that water is scarce, and its beauty is evident in its scarcity, even in a single drop. Contemplating the fall of that single drop might inspire an appreciation of the wonder and mystery of water, even as it flows or drips into the kitchen sink.