Back to Spring 2012 newsletter

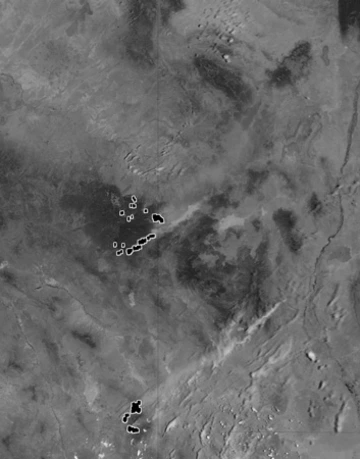

This satellite image of the Wallow fire was captured on June 13, 2011 at 1:45 p.m. local time by Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on the Aqua satellite. Outlined areas show the actively burning parts of the fire. Prevailing winds carry smoke toward the northeast. Source: Jeff Schmaltz, MODIS Rapid Response Team at NASA GSFC.

This year, park and forest managers are deeply concerned about wildfire. The late winter has been exceptionally dry, and it looks like the spring is continuing the same trend. Wildland fire forecasts produced by the National Interagency Coordination Center (NICC) at the National Interagency Fire Center predict significant fire potential for fires greater than 100 acres in large portions of the southwest. NICC produces seasonal fire outlook reports that estimate fire risk by taking into account past and current climate conditions and weather and climate forecasts, along with assessments of the condition of trees and surface fuels such as grasses, shrubs and accumulated forest litter.

Fire potential indicates the likelihood that a wildland fire will require additional resources from outside the area in which the fire originated. Above normal potential indicates significant fire risk. Efforts to predict areas of significant fire potential are aimed at positioning resources where they can be deployed quickly and efficiently when needed. Predictions also assist decision makers and individuals to take steps to protect people and structures from wildland fires.

Fire potential depends on multiple interacting factors. The amount and timing of precipitation are among the most important. Rain and snow pack influence the air and soil moisture, the growth of fuels and their moisture content. Generally speaking, the more precipitation there is the lower the risk of fire. But, it is not that simple. A wet early spring may delay the start of fire season, but the growth of grasses and shrubs stimulated by the rain, combined with a dry late spring, means more fuel for a fire.

The outlook for this fire season is uncertain in part because precipitation forecasts are uncertain. A major influence on our climate, the El Nino Southern Oscillation (ENSO) recently transitioned from La Nina to neutral. Assuming that the ENSO is moving to El Nino condition, the timing of a transition could be very important. Under neutral conditions there remains a good chance for a normal monsoon in southeast Arizona; while a transition to El Nino would increase the probability of a drier than normal monsoon. Although El Nino conditions are associated with wet winters, winter rains would come too late to mitigate fire risks this spring and summer.

Beyond precipitation uncertainties, climate change is likely to exacerbate the situation. There is strong evidence for a warming earth in the temperature record of the last 20 years. Even if climate change brings no decrease in precipitation, the higher temperatures alone will increase dryness and therefore fire risk. Other evidence of climate change is found in the length of the fire season. According to the Forest Service, there are many parts of the country where the season is a month longer than it was in the past.

The fire season has already had a strong start in some parts of the country. Drought and record high temperatures in western Texas set the stage for dramatic series of lightning caused wildfires that burned more than 19,000 acres of land in late April of this year. This occurred in the same area burned by wildfire last year. At almost the same time, the Apache Pass Fire, a fire burning in the Chiricahua Mountains of southeastern Arizona, burned more than 1,700 acres of Bureau of Land Management, Arizona State Trust, and private land before it was contained.

Forestry officials worry that the wildfire season this year could be as bad as it was last year. The Wallow fire last year set the record in Arizona for acres burned—more than half a million—destroying 32 homes and 4 commercial buildings.

Although the Wallow fire was the worst on record, Forest Service officials maintain that it could have been much worse. Forest thinning practices that have gained widespread acceptance in recent years are credited with turning an intense fire moving rapidly through the crowns of the trees to a ground surface fire that was more easily contained. This was especially important at the human-wildland interface, where thinning and other landscape management practices protected structures and people.

Contrast the Monument Fire that burned approximately 30,000 acres during the same period and damaged or destroyed 62 homes and 4 businesses. Forest thinning was planned but had not been done and many structures were exposed because appropriate landscape management, such as clearing brush, had not been practiced.

In these times of heightened fire risk, it is more important than ever to have scientific information on which to base planning and decision making. UA researchers have been engaged for many years in studying the interactions of fire, climate and hydrology. For example, UA is home to WALTER: Fire-Climate-Society model (FCS-1), which is an online, strategic wildfire planning model, developed using the Catalina-Rincon, Huachuca and Chiricahua sky island ecosystems as three of four initial study areas. The model allows decision makers to understand their risks by constructing scenarios and generating maps of the fire hazards and fire risks in their area.

In 2011, a team of researchers at UA received a $1.5 M grant from the National Science Foundation to study fire behavior in the Southwest over the past 2,000 years. The team contains interdisciplinary expertise, including tree-ring science, fire ecology and forest fire behavior, archaeology and anthropology. The project team will be looking into forest fire history, fuels and forests, how human activities have changed them, and the influence of drought and dry conditions.

The devastation of fire is bad enough, but post-fire conditions can amplify damage and delay recovery. After a wildfire the landscape is at risk for additional damage when rain follows the fire. Wildland fires can not only destroy vegetation that anchors soil and minerals, they can actually change soils in ways that lead to drier conditions. Fires can cause formation of a water repellent layer on the soil surface causing water to run off; at the same time they rob the soil of its capacity to retain moisture. These changes can persist for many years.

Because of the loss of anchoring vegetation and changes to the soil, the risk is heightened for major erosion, even mudslides and debris flows in steep terrain. Although gentle rains may contribute to recovery, intense storms and major rainfall events after a fire could be catastrophic.

Post-fire conditions and the responses to them were the subject of the 2012 Southwest Wildfire Hydrology and Hazards Workshop held this April at Biosphere 2, just north of Tucson. The workshop brought together researchers from multiple government agencies with academic researchers and other interested parties to discuss the state of post-wildfire research, disseminate recent advances and coordinate responses to future wildfires in the Southwest.

The workshop, arranged around broad themes, attempted to answer questions that concern the large and varied group of stakeholders. These included: What is the state of the science? What models exist and which model is better in which circumstance? What kind of warning systems have been used and how well have they worked? The focus was on improving responses through research and improved coordination.

Preparation and response to wildfires are key to minimizing damage. Forest managers, emergency response agencies and planners, among others, have a duty to work toward minimizing fire damage; but individual homeowners and business people also have a responsibility to prepare. At the wildland-human interface, it is important to create defensible space around structures. Like forest thinning, removing potential fuel from around a structure can help if when wildland fire threatens. This means, for example, keeping grass mowed and shrubs trimmed, with no accumulation of woody debris near a structure. Arizona Cooperative Extension has detailed information for fire-resistant communities on their Firewise pages at http://ag.arizona.edu/firewise/