A strong El Niño event has been taking place this year. People in Arizona generally welcome the wetter winters brought by El Niño, but in other parts of the world, El Niño can mean droughts, floods, crop failures, and looming food shortages.

Typically, during El Niño winters, a more powerful jet stream will develop north of the equator and steer storms into California and other parts of the Southwestern United States. This year, the Pacific Jet Stream was pushed north of its typical El Niño configuration. In the United States, impacts of El Niño have been felt this winter in the Pacific Northwest; Seattle is having one of its wettest winters on record and ski conditions in Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia have been the best in years.

Typically, during El Niño winters, a more powerful jet stream will develop north of the equator and steer storms into California and other parts of the Southwestern United States. This year, the Pacific Jet Stream was pushed north of its typical El Niño configuration. In the United States, impacts of El Niño have been felt this winter in the Pacific Northwest; Seattle is having one of its wettest winters on record and ski conditions in Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia have been the best in years.

El Niño is the warm phase of ENSO (El Niño-Southern Oscillation), which is a periodic variation in winds and sea surface temperatures over the tropical eastern Pacific Ocean. The cool phase is known as La Niña. El Niño warming occurs, on average, every two to seven years.

There were super El Niño events in 1972- 73, 1982-83 and in 1997-98, the latter bringing record global temperatures alongside droughts, floods, and forest fires. The majority of climate models suggested that the 2015/2016 El Niño would be of similar strength to 1997/1998.

The 2015-2016 El Niño event comes on top of volatile and erratic weather patterns linked to climate change; 2014 and 2015 were the hottest years on record, with the Pacific Ocean already warming to an unprecedented degree. Evidence is emerging that climate change will increase the odds of stronger El Niño (and la Niña) events according to the World Meteorological Organization.

The ocean stores the vast majority of the Earth’s heat. While heat storage is stable over decades to centuries in the depths of the ocean, the temperature at the surface can vary from season-to-season and year-to-year. During an El Niño event, sea surface temperatures across the Pacific can warm by 1–3°F or more and warmer conditions can last for a few months to two years. The unusual warmth is coupled with a slowdown of the easterly trade winds, as well as increased rainfall and a drop in surface air pressure in the central tropical Pacific. These disruptions to the normal air movements in the tropics affect the mid-latitude jet streams, which is how El Niño can affect weather around the world.

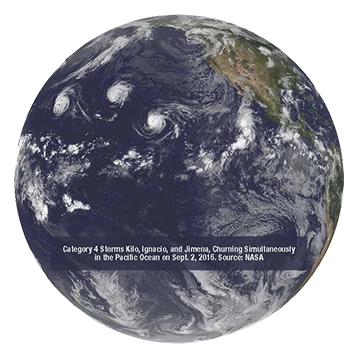

El Niño influenced weather systems bring more intense cyclones in the North-Western Pacific and more frequent cyclones in the South Pacific are typical. El Niño events tend to enhance the hurricane season in the Pacific and depress the Atlantic hurricane season.

Globally El Niño is associated with patterns of weather extremes. More precipitation is expected in some places, while others may receive none at all.

It must be emphasized that these impacts are likely but not certain. The stronger the El Niño, however, the more likely its impacts become. Some correlation has been observed between the strength of the El Niño and the severity of the effects, but there are no guarantees here either.

Oceanic and atmospheric indicators suggest the 2015/2016 El Niño has peaked; however, countries continue to feel its effects. In South America, southern Uruguay, Paraguay, and southern Brazil have received much more rain than their long-term December–February average. Thousands were displaced in Argentina and Paraguay when the Paraná, Uruguay, and Paraguay rivers overflowed in late December.

The northern portion of the continent has been dry. In Central America, El Niño was associated with serious drought in Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador. Some Caribbean countries have also suffered drought. This pattern is consistent with expectations in El Niño periods.

Also consistent, so far, with El Niño’s typical impacts have been Africa’s rainfall patterns–wet in portions of Kenya and Tanzania and dry in southeastern Africa and southern Madagascar. In addition, predicted dryness has been seen throughout Indonesia, South and South-East Asia, and northern Australia, and rains in southeastern China.

El Niño has perhaps been most pernicious in Africa, as drought ravaged much of the south of the continent. Southern Africa, including Zimbabwe, Botswana, Namibia, Angola, South Africa, Lesotho, Swaziland, and the southern half of Mozambique, tends to see a drier December–February during an El Niño. Areas of this region, especially South Africa, were already very dry, after a failed monsoon last year. In 1992, El Niño caused the region’s worst drought in a century, affecting around 86 million people, 72 percent of the population. This year, Zimbabwe declared a state of emergency and an estimated 26 percent of Zimbabwe’s population, around 2.4 million people, is now considered food insecure due to dying cattle and failed crops.

Cereal production will be significantly reduced in specific countries resulting in more volatile prices according to the World Food Programme. For instance, maize production shortfalls led to a surge in prices in Southern Africa. In highly import-dependent regions such as West Africa, consumers face food insecurity due to increased grain prices. The food security effects will be worse for regions like the Horn of Africa, which are already suffering cumulative effects of past poor growing seasons. In Ethiopia the impact of the failed spring belg rains was compounded by the arrival of the El Niño weather conditions that weakened the kiremt rains essential for feeding 80 to 85 percent of the country. This greatly expanded food insecurity, malnutrition and devastated livelihoods. In addition, an estimated 5.8 million people require emergency water supply and sanitation.

In other areas of Africa, El Niño is causing major floods, landslides, and increased frequency of diseases that destroy cattle and crops. Excessive rainfall triggers outbreaks of waterborne diseases such as cholera, typhoid, and vector-borne diseases like malaria. Increased risk to livestock can accompany excessive rain, such as Rift Valley Fever outbreaks.

As of December 3rd, floods had already displaced 144,000 people in Somalia and an estimated 76,000 people in Kenya, according to the National Disaster Operations Center. Localized heavy rainfall resulted in flooding in parts of Mozambique and Madagascar while other parts of those countries were suffering drought. In Tanzania, flooding occurred in various regions, including Dar es Salaam, the capital city.

Historical records of previous El Niño events suggest that the likelihood of the current El Niño being followed by La Niña is the same as a return to neutral conditions, during the second half of 2016. El Niño and La Niña events typically only last for nine to twelve months and re-occur every two to four years. Flip-flops from a strong El Niño to La Niña are not unusual. Should it occur, a La Niña could exacerbate the negative effects in countries that have experienced El Niño conditions.